Where does design fit into the development life cycle?

Every now and again I walk into a new team and more regularly than not, there seems to be a disconnect between the design- and development functions.

Understandable.

Rewind 20 years. Design thinking and design was something that belonged mostly in advertising agencies. The typical software development team didn’t see the need to include a designer.

Fast forward to today and as a product person, sometimes I still feel like a new toy that no one knows what to do with when walking into a developer heavy team that’s never worked with designers before.

They know what results they want, but they’re unsure how to practically integrate it into their existing development process. To exaggerate the disconnect, the thinking styles of designers compared to developers are very different. It’s rather like one team talking Mandarin and the other Spanish.

Crossing this gap between the different thinking styles can be challenging. Anyone who’s new to Test Driven Development will understand this, as it requires you to think in a totally different way than what you’re used to and comfortable with.

When, however, you include a good UX/UI designer or Product Manager, the results are magical. It’s the difference between Microsoft and Apple back in the day. The one aimed at being feature-rich and affordable, while the other aimed at being simple, useful and beautiful, and creates a niche following that lasts long after the founder’s death and who is willing to pay a premium to be part of this exclusive club.

Being feature-rich, of course, is not bad in itself. It’s usually just better to solve a problem (design) and build the right thing before starting to build, an approach most developers I’ve worked with prefer.

If you’ve ever found yourself frustrated filtering through all the junk on the Play Store searching for a useful app, you probably know what I mean.

Is / Is Not

So let’s look at a few common misunderstandings when it comes to design.

Design is more than aesthetics

Many people tend to think of design as esthetics only. And yes, if you only include a graphic designer in your team this might be true. But the Product team is not only there to make something look pretty. In fact, a Product Manager and UX designer might not be able to draw well at all.

The design thinking perspective (which is very similar to the Lean Startup process) is a process that takes a fuzzy goal and turn it into a tangible prototype (in most cases a mock-up).

In other words, they turn guesses and ideas into educated decisions based on facts. Their primary focus is to do research and validate ideas early and cheaply. It is after all much cheaper and faster to change a design (provided it is broken into small enough parts) than to rebuild software that didn’t get the desired response from your user base.

Good design is good problem solving

Primarily, the “product” team owns the problem. They make sure that you’re solving the right problem — is it useful and is it the most important priority that will add the most value to the users?

The product team spends time to clarify the problem and come up with possible solutions which they present to the technical team who will take over the implementation part.

The double diamond approach below is a tried and tested process to turn a general problem into a specific problem (prioritize), and then into a possible solution that is validated with the users before it is handed over to the development team to build.

Image from https://www.gdm.gent/design-meets-research/hcd/

The “development” team, on the other hand, primarily owns the solution — the how it’s done. They make sure that the problem is robust, safe, efficient, and maintainable. They take the prototype (usually a mock-up or concept) from the product team and figure out how best to build it.

Comparing it to building a house, the architect and interior designer would be the “product team”, while the engineers, builders, plumbers, and everyone else required to transform the idea on a piece of paper into something tangible, is the “development team”.

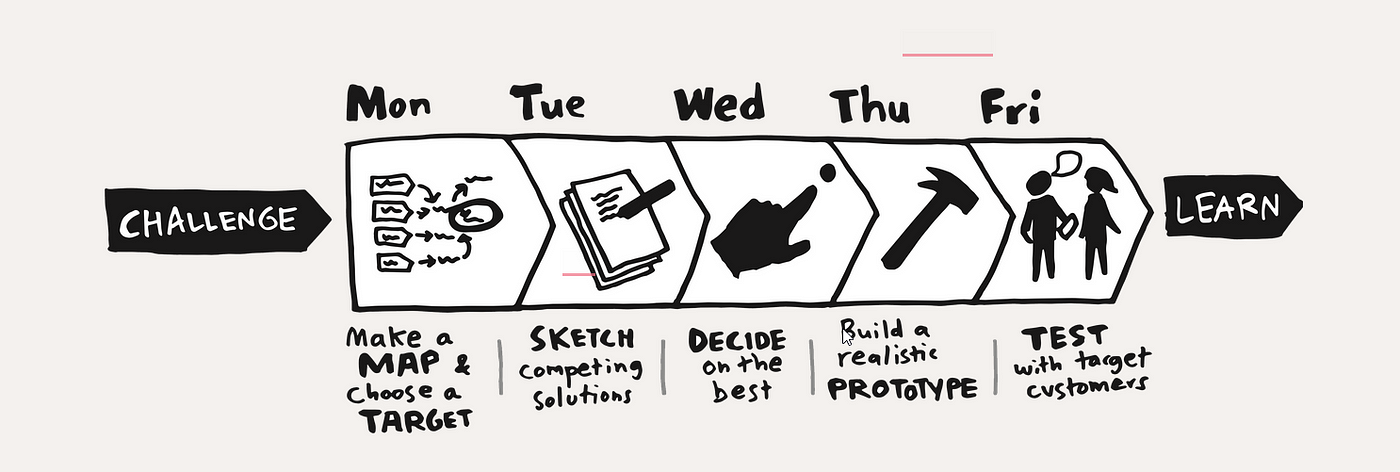

To design sprint or not to design sprint

Google made Design Sprints popular and with that opened the door to include a design team into the process of development. Design Sprints — the Google way — is, however, most suitable for startups or products looking for new ideas. Most teams don’t need it. Or at least not in the focused, 5 day format.

Image from https://www.thesprintbook.com/the-design-sprint

A design iteration — the non-Google way — can take many forms. What is most important is to include all the stakeholders early on. The reasons being:

- To ensure you’re meeting the customer’s expectations and goals, and;

- To design something that can technically be built by the team responsible for it.

That doesn’t mean, however, that everyone should do everything together. It could very well mean a number of workshops where everyone does everything together. But in reality, this is rarely useful for an existing product.

The purpose of the design sprint is to prepare the requirements adequately so that the developers can spend their effort in figuring out how, not what to build.** This means ensuring it is needed, useful, and the most important thing right now. It also means that any unknowns will be identified and turned into knows before the developers have to start building.

Mindset matters

More and more developers are starting to see the benefit of including a good Product Manager (not to be confused with a Project Manager who only owns the process, not the product) in a software development team.

Yet, many developers simply don’t see why they need a Product Manager (or Product Owner or UX designer…) if they can find ready made assets online and use libraries to build forms, pages, etc.

It’s hard (or maybe impossible), however, to see the forest from the trees. It’s much more efficient to have someone look at the forest from afar while another is amidst the trees trying to navigate their way between complex code.

The mindset required to think about a user experience compared to building a rather complex piece of software is completely different. The one requires an external, objective viewpoint — like observing at something from the outside. — while the other requires a more subjective viewpoint — like examining something from within.

Are you building the right thing?

Another, more pressing reason is that as much as 80% of software isn’t used by users. When presented with a cluttered and feature rich interface users will probably focus on the 20% features they are already familiar with.

That means a substantial chunk of your development effort goes towards unused software. Maybe because they can’t find it, or more probably because it doesn’t help the end-users’ achieve their goals more effectively.

That’s a lot of waste!

Including “product” (a collective word I use to refer to everyone involved in the design process, including a Product Manager, a UX designer, a graphic designer and possibly a Business Analyst or Product Owner) perspective increases the probability that what you’re building is useful and adds value to the user. It’s thus usually a lot more productive.

A recipe for an integrated development process

So now that we know why design is important, let’s look at how to practically include it in the process and where the boundaries are.

1. Customer brief | Discovery

The first point of contact is usually a result of a pain point or a desire to create something innovative. The customer will brief the product team (and possibly a technical lead) or end-users will complain about something they feel is important to them.

I find including the technical team in the process at this early stage is less useful than helpful as everything will most probably change from brief to planned sprint or iteration. I would much rather record the session and make it available to the technical team as optional viewing should they be interested in it than including them in the brief in-person.

At this early stage, the primary purpose of the product manager / product owner is to determine what success might look like for the customer. What does the customer want the users to do and how will they feel when the pain point is resolved? What will be different? What will it look like when the problem isn’t there anymore?

2. Research | Reality

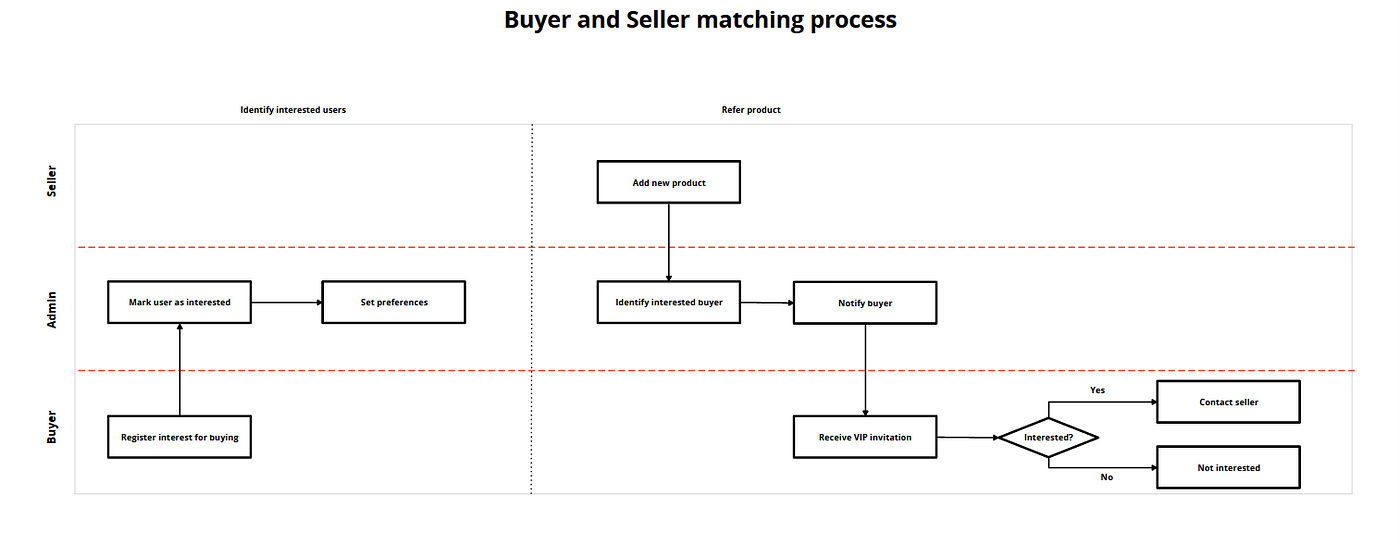

Once you understand the desired outcome, the next step is typically to spend time researching what is already in place, what others are doing, and what end-users need, starting with the process flows of what they currently do.

Roads are made by walking. The best designed software support worklows and real-life processes. Start with mapping out the processes, for example:

Simple process flow in Conceptboard

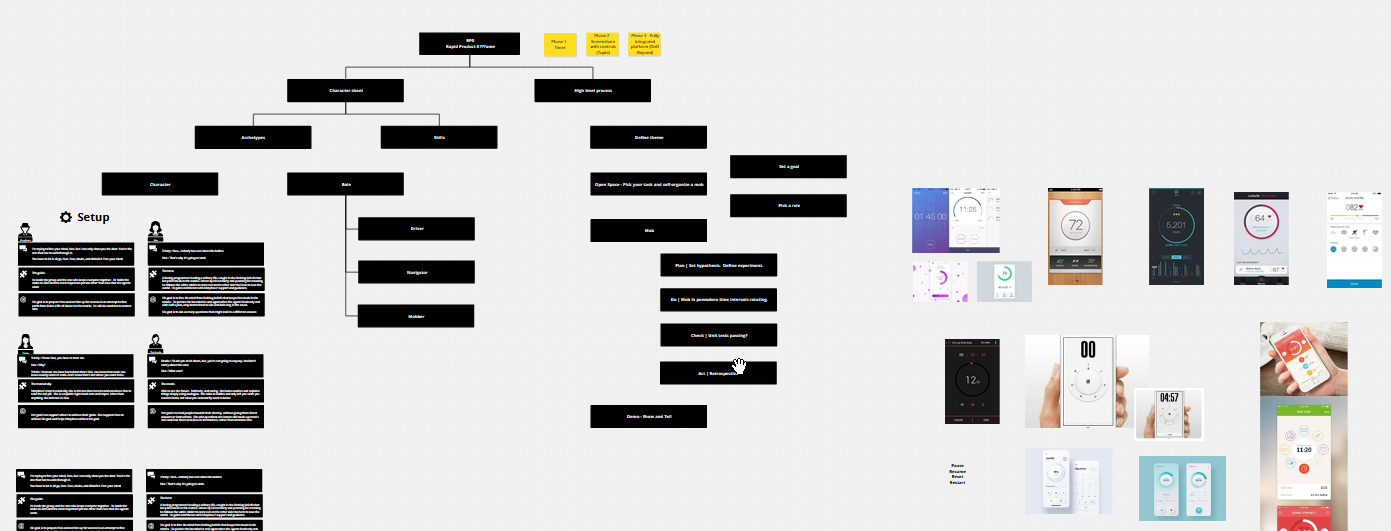

It is also useful to have a mood board with some inspiration as below with some sample timers for a timer app:

High level product scope with a mood board to serve as inspiration.

A competitor analysis to identify what’s missing is also useful at this early stage, for example comparing what aspects of a competitor you love, and what you wish were there that currently isn’t:

Simple competitor evaluation to identify what’s missing.

I like to use Conceptboard for this phase as it’s specifically designed for this and has an infinite canvas that grows with your product.

Once the foundation is laid and you know what is needed, the next step is to design a rough concept. This is not intended to be a pixel-perfect design, but rather a tangible artifact to enable a useful discussion and the ability to make changes fast, and collaboratively. The goal is to visually communicate rather than finalize a design, thus I usually don’t spend more than a few hours on this.

In many cases this is enough to allow the developers to start building, leaving enough room for them to add their contributions. However, in a new product design the next step would be to create more detailed designs and workflows.

After reviewing it with the technical team and getting their input, present the key research insights and high-level concept to the customer for discussion.

The goal at this stage is to get feedback, not approval.

3. Planning and design | Iterative approach

Once the customer and technical team feels confident that the solution is adequate and realistic, a few things happen:

- The product manager breaks down the concept into smaller chunks which will become individual user stories that can deliver a complete valuable feature at the end of a maximum one week iteration.

- The graphic designer finalizes the designs and identify or update design system components.

- The technical team negotiates with the Product Manager to find a balance between scope and time, following the Basecamp approach to shape work.

Rather than the technical team saying how much time it will take to do something as in traditional Scrum, the Product Manager dictates how much appetite they have for a specific feature and then negotiate the contents to fit into this budget. Thus, estimations are product-driven rather than developer-driven.

Again I like to use Conceptboard for planning as it is extremely flexible to create a layout showing the planned iterations and status of each smaller chunk of work in one view. For design I prefer Figma but any tool that is accessible by the whole team and easy to navigate is acceptable and depends on the graphic designer’s preferences.

4. Building | Development

The next step is to hand over the first iteration to the developers, who will effectively work in a black box, unless something pops up that require input from the Product Owner, similar to what Scrum was designed for.

The Product Manager has no say as to how the developers build the artifact that was handed over to them. They rely on feedback from the developers to know if there’s an issue in a push rather than pull approach, limiting interruptions to the developers as much as possible.

They will typically start working on the next concept while the developers are building.

At the end of the iteration, the developers demo what they’ve done in a production like environment where the Product Manager can interact with the product and ask questions similar to the Scrum review meeting.

5. Validate | Approve

At the end of the iteration and after the demo, the Product Manager or product team validates it. The validation process aims to ensure that the right product was built and that it integrates without any unexpected error into the larger system before handing it over to the customer for final validation before it is deployed into production.

Once an iteration is approved, a retrospective looks back at the past iteration to see if there’s anything that can be improved for the next one before continuing with the next iteration.

Bridging the gap

Scrum changed the world. But it is a process framework for developers and most problems I see are not building the thing right (aka development), but building the right thing (aka design).

Being productive is not just about ensuring that you are optimizing the way you do things. The most important aspect of productivity is to start with a clear goal. This is where design fit into the process.

So next time you’re struggling to prioritize, or frustrated with ever-changing requirements, consider starting with the end in mind.

If you need help streamlining your development process, visit https://www.funficient.com/services.html and start the conversation by booking a complimentary first call.

Original article published on: https://funficient.medium.com/where-does-design-fit-into-the-development-life-cycle-342c8dc12fbc