Design better products with game thinking

A simple, but not simplistic, design approach.

UX designers and Product Owners spend a lot of time researching good products in order to design something you hope will engage your audience for the long haul. For me, it’s like building a puzzle, taking one piece from this product and another piece from another successful product I like and weaving it into a single tapestry. It can, however, become overwhelming for larger products. Losing track of the core intent and value proposition, even for an experienced designer, is easy. That's where the gamethinking framework shines.

Changing priorities

The biggest issue I see in software development productivity is that teams loose focus of what’s important. They get so busy building that they forget why they are building it in the first place. They focus so much on one piece of the puzzle and the intricacies of how that part should work that they often loose sight of the bigger picture.

I consider myself a big picture perspective person. I struggle when I can’t see the bigger picture. And even with this natural skill that I’ve developed even more over the years I too often get lost in the details when building or designing software.

Until I stumbled upon the Game Thinking framework by Amy Jo Kim, a game designer and entrepreneur. I resonated with her as she claims to blend game design , startups and agile practices — all the areas I am also passionately interested in — and wanted to learn more. After attending a few of her webinars I tried her product teardown framework — a mini UX audit focused on evaluating long-term engagement of products.

I evaluated Luno as part of a user research project for designing a crypto-currency self-bank solution and realized I struck gold when my entire body responded with an audible sigh of excitement and relief as I looked at the summary at the end of the process. At a glance, I could see the entire user journey to mastery. While using Luno I realized something bothers me but I couldn’t quite articulate it until I put all the puzzle pieces together. Suddenly it was clear why I lost interest after a few weeks, even though on the surface it was a good product. The Game Thinking product teardown pinpointed the problem with accuracy that enables action to improve it.

The Game Thinking framework combines the progression levels of game design with the lean startup model, agile user stories and the general marketing cycle.

Building a whole product

The most fundamental aspect of the Game Thinking framework is the game design user journey mechanism called progression levels, something inherent and fundamental to the game design process. Game designers spend a lot of time researching human behaviour and motivation. They understand it better than most industries as their entire reason for existence can be narrowed down to their ability to engage people to play a game over everything else in their life at that moment. Unlike retail, financial services or medical services, games are pure entertainment. No-one has to play a game. You choose to play a game. If it’s not engaging enough you’ll put it down and move onto something else.

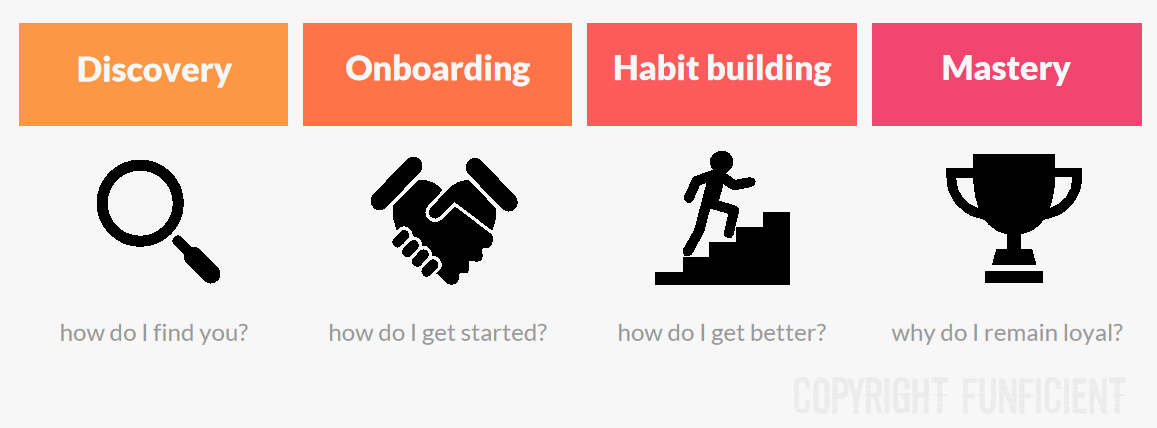

Summary of the four main phases of the Game Thinking framework.

They research the art of engagement and mapping out the progression levels are their primary compass to ensure they focus on engagement first. This process is similar to the marketing sales process and starts off with getting a target user’s attention in the Discovery phase. The Discovery phase attempts to get a new user to become aware and interested in the product and not necessarily part of the product but essential for the product life cycle.

The next phase is focused on helping a new user to get started as easy as possible in the Onboarding process. Product designers can learn a lot from a game designers approach to onboarding. In game design the complexity emerges throughout the game play with new features being unlocked as you progress. It starts off with one core mechanic in training levels which is so easy that it is impossible to get it wrong. Imagine redesigning a complex system like the Adobe suite or Blender to up-skill new users rather than overwhelm them with new features all at once? A lot more users will use a lot more features when they are guided through the complexity rather than just pushed into the deep end to swim or sink.

“Fun is just another word for learning.” — Raph Koster

The next phase is the heart of a game, and a product. In the Habit Building phase the goal is to get get users to come back each day. To fully appreciate the importance of this part of the process I recommend reading “A theory of fun” by Raph Koster who summarizes “Fun is just another word for learning.” The Habit Building phase is designed around a core learning loop with the game thinking behind it that you want to make the users better, not the product. This constant empowerment of a user makes it addictive and psychology is at the core of this phase.

Finally, the Mastery phase is for those select few hard-core players who become the ambassadors for the game. There are usually only a handful of users who become masters at the game but these people will invest a lot of effort into making the product better and selling it to their friends. Microsoft and Google, amongst others, strategy and reason for success to a high degree is because they only employ those people who have proven themselves to be true ambassadors of their products. To be considered for an employee at these giants you have to breathe the company and can even be considered as zealots who will do pretty much anything for their company because they believe in it so much. This is a super powerful, although not entirely healthy, approach to grow a company or product’s reputation and the mastery phase focuses on these handful of users to build brand ambassadors.

Succinct requirements with agile user stories

The next layer that makes the Game Thinking framework so great is that it adds the agile method of stating requirements as user stories in a set recipe to ensure it is succinctly focused on value delivery. It builds a bridge between the product’s vision and actionable steps.

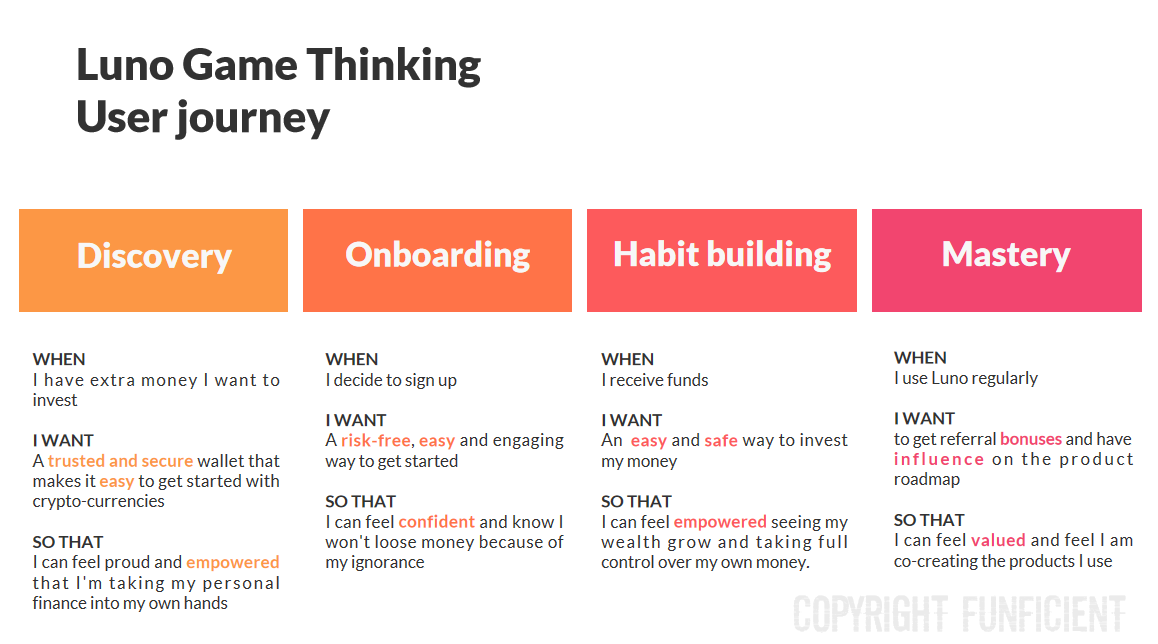

High level user stories for each phase of the Game Thinking process phase.

Requirements can get messy.

When you come from a business analysis background as me you might have stumbled upon death by requirements, either in various versions of thick documents filled with business requirements, functional specifications, and technical specifications, or requirements management systems such as JIRA where each requirement and error is logged in a system with a unique identifier. No matter how good, no one person can ever know the exact impact of a single requirement and no one document usually contains everything both business and developers need in order to build it. In most cases, more time is spent on managing the requirements and errors as a result of oversights than building new features. Messy. And unproductive to say the least.

When, on the other hand you come from a UI design background, you might be familiar with design systems and death by screens. Equally messy, but in a different way and slightly more comprehensible by the average person than the piles of documents produced by business analysts as a picture is less prone to being misunderstood than words. Still messy though. And still unproductive, and potentially more expensive.

Right in the middle of these two extremes, however, is a sweet spot called user-, or job stories. If used incorrectly these stories might feel like exactly the same mess as the other ways, but if used correctly, it brings clarity and focus like nothing else.

Agile software development introduced the concept of user stories, which in effect is just a small portion of a much larger requirement with a business benefit and target audience in a single sentence.

AS A

I WANT SO THAT .

For example, AS A new crypto user I WANT to buy crypto currency with my fiat bank account SO THAT I can participate in the benefits of crypto currencies. This works well when there are a number of different users, however, in my experience few systems truly have different personas using it. Or, it is only valuable when starting off with a new system.

Job stories solves this problem by removing the persona and focusing on the trigger of the event. The user type of a user story is omitted and the format now becomes WHEN

WHEN

I WANT SO THAT .

For example, WHEN I have extra cash to invest I WANT an easy way to buy crypto currencies SO THAT I can feel empowered taking full control over my personal finances. The job story for each phase is focused on communicating an overall intent. It gives direction and focus. It creates boundaries to make it more achievable to build one complete thing rather than a bunch of parts that doesn’t quite form a whole picture.

For each of the phases within the user journey or mastery path, depict a primary intent job story. When you get into the details of each phase, these stories will guide you towards your initial intent and help decision making. Each time you decide to add or build a new function, use this primary story as filter. Will it enable the user to easily buy crypto currencies? Will the user feel empowered with the design?

If the answer is no, re-evaluate whether the function should be built or whether the designs should be adapted to more closely align with the original intent.

Better products need better thinking

Trying to keep sane when working with complex and complicated products has little to do with your memory skills or cognitive abilities. The human brain can only process roughly 4–8 items in working memory. You can either try to prove science wrong, or you can work with what science has proven as optimal and build better products incrementally.

The Game Thinking framework is a simplified (but not simplistic) tool that allows you to design a comprehensive whole product. On a single page, you can see the entire product mastery journey as a high-level zoom that will enable you to think better and thus build better products.

See how I used the Game Thinking product teardown evaluating Luno here.

Originally published in UX Collective https://uxdesign.cc/design-better-products-with-game-thinking-3cde5ce21c26