To Document, or Not to Document. That is the Question.

Discerning the need for documentation in an agile world

It all started one early morning in Cape Town at a buzzing coffee shop with real wooden table tops (one of my requirements to decide whether I like a place or not), good coffee and of course, good company. While most Cape Townians were still fast asleep at this early morning hour, a handful of true agilists lived up to the challenge and met up in search of answers to life, the universe, and everything. This time, one of the questions posed was what documentation you need to be fully agile.

Sticky notes, good coffee and good company.

A waterfall world is often characterized by death by documentation. There are business requirements, functional requirements, technical requirements, detailed test scripts, and project plans to name but a few of the mandatory documents for any single project.

Documentation is definitely one of the biggest stumble blocks to overcome in order to find balance between agility and structure. What to keep and what not to keep.

Many people believe that when you go agile, documentation is no longer needed. That’s not true at all. Agile is not about getting rid of documentation, it is about questioning the value of documents to decide what should be created, how it should be created, and where it should be stored.

Myth — You don’t need all the documentation from a typical waterfall implementation when you implement agile.

An agile world is not free from documentation at all. It’s just that it looks different. Where previously everything was written down in Word documents following a rigid and standardized documentation control process (which no-one knew existed or cared to follow in most cases), in an agile world only the most necessary documents are written down on whatever material is most useful and most accessible. For this user story and this sprint.

Sometimes it’s handwritten scribbles on sticky notes, like in the photo, with the purpose to provide structure. Sometimes it’s a sketch on a whiteboard, intending to clarify or conceptualize ideas. Sometimes it’s a mind-map on a scrap piece of paper, aiding the completeness of a thinking process.

Sometimes it’s typed up neatly on a more structured user story or document shared on Google Drive to aid understanding and collaboration. Sometimes it’s an ever-changing wiki and sometimes it’s a beautifully designed user persona or product vision printed in full color and put on the wall.

And sometimes, it is a version-controlled word document, printed and signed, or a 100-page artifact. See, there’s really no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to documentation in an agile world. It all depends…

Agility is about weighing up the value of the documentation compared to the value of doing the work. It’s about “uncovering better ways of developing software” and valuing:

Working software over comprehensive documentation

The question is. How do you decide what is valuable or not? When is it enough? When is it good enough?

Decisions are best made when you weigh up the benefits and the disadvantages. Let’s look at the up- and down-side of documentation as it applies in the agile world of software development, followed by some guidelines to help you decide as inspired by this Lean Coffee Meetup:

The downside of documentation

Documentation is great, except when it’s not so great. Here are a few reasons supporting the case against documentation:

Good enough is good enough. Perfection is a waste.

- The moment you write it down, the information risks being outdated. In a fast moving world, often, the requirements change faster than the time it takes to write it down. Or, it is faster to build it or create a mock-up than write it down. That’s why I love sticky notes and pictures.

- It’s bound to be misunderstood. Words are read through filters based on background, experience and skill. Ironically, we write things down to remove the possibility of making assumptions, yet in reality, each person has their own biases when reading anything based on their background, experience, skill, and emotional state. In most cases, what is written down is not what is understood. Read more on my view about communication in The Real Answer to Life, The Universe and Everything.

- Written documentation is slow. That’s why infographics became popular — a good image is engaging, “tricking” people to look at or read information they wouldn’t. Writing down the same information in words is much slower than simply doing the work in many cases. Reading it is as slow and often painful and most people scan through information missing the very details which you thought made it valuable to write it down.

- If you can’t find it, it is as good as not having it at all. How often have you heard someone say there should be a document about that somewhere in the repository? We actually had a joke once that if you want to hide information, be sure to put it on the wiki, because no-one will ever be able to find it ever again. Your documentation is as good as the ability to find it when you need it.

- Documentation is expensive. Documentation is often created by the most expensive resources in the company. It’s viewed as insurance on intellectual capital companies pay for. Specialists, architects and highly paid consultants are asked to write down everything they know in the hope that somehow, by writing down information, the reader will now gain that same knowledge.

But documentation is not always bad.

Documents help clarify grey areas.

The value of writing it down

Documentation is extremely valuable in certain cases. Here are a few of the most important reasons supporting the case for documentation:

- To remember things. According to science, our working memory can only handle between 3 and 8 items at any given time. Our optimal capacity is 4 items before we start getting confused. When you have more than 5 items to remember, it’s a good idea to write it down.

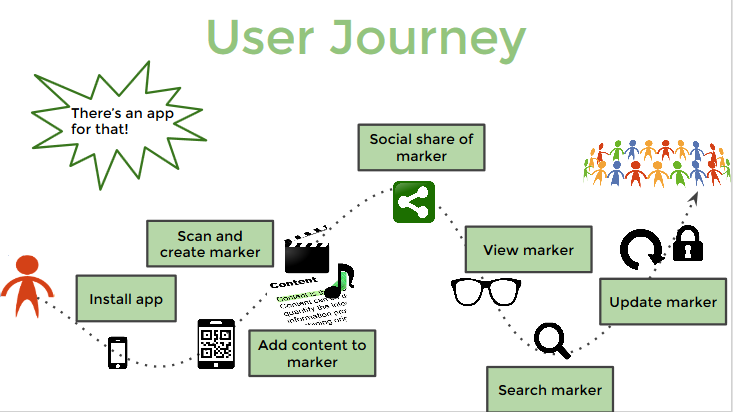

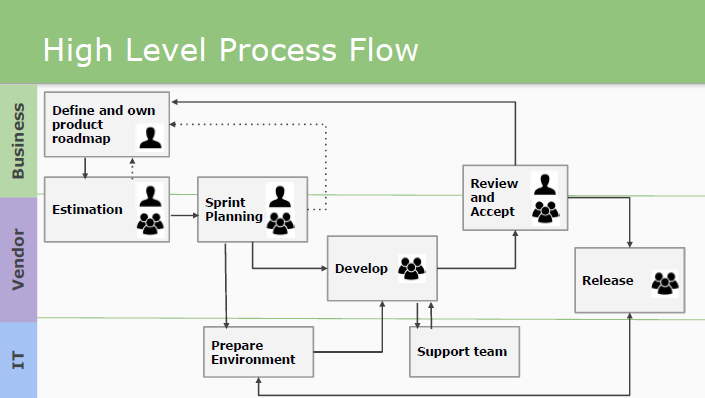

- To simplify complexity and to clarify grey areas. An architect draws a model of a building to conceptualize a very complex idea into something more tangible. Models of any kind are useful to simplify complexity and clarify boundaries, whether you’re an architect, a fashion designer or a software engineer. A context diagram, ERD (entity-relationship-diagram) or process model all simplify overly complex systems allowing us to see the impact of changes at a glance and remove any grey areas.

- It’s a cheap way to validate ideas. How often have you spent hours talking about something and days or weeks building it, just to find out that’s not what the other person thought you discussed? Having something concrete to look at and criticize without spending too much effort is much quicker and more accurate than having long discussions.

- It explicitly states expectations and agreements. Contracts remove grey areas, ambiguities and uncertainty. It explicitly includes or excludes certain conditions, which provides a level of psychological safety. When you sign an agreement, you know the rules of the game you’re about to play. You know what’s expected from you, what you’re entitled to, and what to do when things go wrong.

- It adds credibility to information, making decisions easier. Supporting documentation providing details indicates the level of due diligence that a person did in preparing it, which in turn increases trust in the information and thus makes decisions easier. It shows you’ve done your homework and put some thought into something.

Documentation Cheat Sheet Checklist

Taking these advantages and disadvantages into consideration, here’s a quick reference guide to help you decide whether to document something or not:

1. Who is it intended for?

Most documentation is useful to someone. But what is useful to one person is not necessarily useful to the next. I’ve had bosses who love detailed documents. Others wanting only a one-page dashboard. Some developers need written down requirements, others like pictures and a quick chat. The most important question to ask before you start writing it down is asking yourself who needs it and why.

Depending on whether a team is co-located or distributed also increases or reduces the need for documentation. Are they in the same time zone? How senior or junior is the team?

Document only what you need and forward only what is useful to the audience.

2. Is it valuable to the customer?

Ask yourself whether a customer would pay for the documentation you are about to create. If the answer is yes, do it. Most probably, however, no-one is going to read your 100 page requirements specification, including the developers doing the work. So don’t do it just because that’s what was done before.

Agile is finding better ways to do things. Each sprint. Each story.

3. Are there any legislative or audit requirements?

Most organizations have some form of legislative requirements related to documentation. The healthcare industry requires very detailed records whenever a requirement is related to patient safety. The gaming industry requires a standard set of documents with specific information on it in order to be certified legal. The finance and insurance industries require user privacy to be protected, while the tax authorities require a set of standard information to be collected and stored.

External providers also sometimes mandate certain documentation requirements that might not be legally required, such as external auditors.

To decide on the value, first and foremost, know what documentation is required and why. Often documents are remnants of a predecessor or previous requirements that are no longer valid. Only by asking why it exists can you know whether it’s still valid or not. You can safely assume it was useful in the past, otherwise, it wouldn’t have been created. The question is whether it is still useful.

How easy can you find what you’re looking for?

4. Will it make maintenance or decisions in the future easier?

What if you had to come back to this feature or code in 6 months from now? What would make it easier for you to hit the floor running?

Do you need every detail of every bug? Or just the essentials?

Are there legislative requirements requiring me to keep this information? In what format? How can I find it easily in a year from now?

5. Will it help you improve in the future?

Trends and graphs over history are extremely useful to show progress, patterns, and bottlenecks. By keeping the history of key statistics, you are able to predict future work, see whether an improvement is working or not and finding areas to improve.

Keep data and documentation that will help you see trends or compare information.

6. How frequently does it change? How long is its lifetime?

A binding contract doesn’t change often and the lifetime is usually long. A bug report, on the other hand, might change every hour and might have a lifetime of a couple of hours.

When information changes frequently, use sticky notes and photographs and rely on conversations. When it changes less frequently, like a contract, spend time documenting it professionally. The longer the lifetime of an artifact, the more useful it is to write it down, as memory fades over time. Write down bug reports and requirements only if you’re not planning to fix or implement it immediately.

7. Will it help you reach your goal?

Finally, the most important question of all. Will documenting this help you reach your goal? Will it help you keep focused, removing distractions that result in unnecessary details (also called scope creep or easter eggs)?

Will you be able to deliver a story that will be accepted by the Product Owner with the details you have? Does it have all the information you need to build this feature without unintentionally breaking something else or require you to stop and start every 5 minutes to get information you need?

Is it useful? Is it necessary?

Waterfall documentation was easy. For everything, find and fill in the template. If it’s not relevant (or in some cases if you don’t understand), just write Not Applicable.

Agile documentation is not that easy. There’s no right or wrong answer when it comes to what to document and how. It depends on more variables than what is possible to mention. The team, the project, the client, the organization and the relationships, to name a few.

All agile documentation does, however, have two things in common. It is useful (for this project or story) and it is necessary. So next time you’re wondering whether to document something or not, just ask yourself these two questions:

“Is it useful? To whom?” and “Is it necessary?”

Disclaimer: I have no affiliation with the Scrum User Group or the organizers of the Meetup. I just love writing and telling people about things worth knowing about or could be valuable to share.

Originally published on Medium: https://funficient.medium.com/to-document-or-not-to-document-that-is-the-question-fcb534d0357b