Testing complex systems with play

Accelerated results with playful design

I’ve been testing software for a long time. In fact, my first job was as a tester. In an industry which evolves faster than what is possible to keep up with, I wouldn’t consider myself — or anyone as a matter of fact — as a master in software testing, but I have completed the 10, 000 hours of mastery required to qualify me as, at least, competent in the art of software testing.

Over the years I’ve seen testing being more integrated into the developer role with Test Driven Development (and Behavior Driven Development) and I remember the great relief and freedom that exploratory testing brought to the industry. Then there was the introduction of crowd sourced testing which solved the problem of configuration related issues, even though it comes at a high cost and doesn’t guarantee higher quality as testing is not done by qualified testers.

Other than that, the field of software testing has changed very little over the past decade or two, while the complexity of what we’re testing has increased exponentially.

A short history of everything...

Testing was easy back when the methods were created. A detailed requirements specification was the baseline from which you drew up a detailed test plan. You then executed each step of the plan meticulously in sequence until completion.

O, the good old days when things were simple…

Systems had clear boundaries as integration wasn’t common. Each product was its own safe little black box where you had full control and a methodical test plan was a very good idea.

There were little to no competition with mostly niche markets paying a premium for automating a part of their value chain specific to their needs. The users’ primary roles were to input data into the system. Catering for multiple use cases for a single function was not common. Rather, the software developers told the users how to use the system. Comprehensive training courses on how to use overly complicated systems were standard.

But then the internet became more commercially available, with the Google app store and high quality MOOCs (massive open online courses) allowing anyone to build anything and make it accessible to the entire world. On top of that open-source software became popular and choices became abundant. You no longer had to pay expensive premiums to use software as there were an abundance of free or lower costed options available. Slowly but surely the focus started shifting from niche and technology driven to personalized and user driven solutions.

And then, of course, the shadow side of software started emerging with the growing competition to own data - Google and Facebook at the fore-front of the race. Their solution to owning the data was simple — control the log-in point. API’s (application programming interface - essentially a public access point to a closed system) to handle user log-in was introduced which made it easier for the user and integrations via API's became a user expectation. If you wanted to compete you had to integrate to the big players and today API's has become an essential part of software development. Which is great for the users and the data gathers on the other side, but terrible for the software developers who no longer had full control over what they were building and when it changes.

Testers were suddenly overwhelmed with all the possible permutations to test and quality declined despite the longer hours and more fancy tools to automate parts of the process.

Complicating complexity

Suddenly, test planning and design had to take into consideration different devices and configurations far beyond anyone’s control. Integrations and personalization further added to the already complex systems making it impossible to use the existing software testing methods to ensure coverage.

Where a decision table to plot the possible test cases were a great tool to ensure coverage, now a decision table is inadequate for even a small step such as user onboarding. The vast number of permutations and variables are simply too many. You have to test self sign-up as persona type one, two and three; self sign-up via invite from persona one, two and three; self sign-up with an existing invite active; sign-up with multiple invites pending from different invitees; sign-up using facebook, google, twitter, email, phone, different types of phones, different browsers, different locations….

You catch my drift.

And that’s just signing up. A mere prerequisite to actually using the system.

Even with an unlimited budget and able to afford adding more testers or automation tools, by the time they finished the planned tests the market place have already shifted so much that your solution would no longer be a fit for what it was designed for.

So what do you do?

You could scream and pull out your hair while throwing around your weight as test manager demanding more from your already overworked testers. And it might even work for a short while.

But you don’t use a hammer to fasten a screw and you don’t use a muffin tray to bake a bread. So what if there was a better, easier way to test complex systems?

Playtest or Playful test?

“The creation of something new is not accomplished by the intellect but by the play instinct.” — Carl Jung

In gaming the equivalent of validation or acceptance testing is called “playtesting”. When I first heard the word, I was immediately intrigued. Playtest?

Very interested in play mechanics and using play as a tool to engage and motivate teams, I explored a bit more. What I discovered through observation is that playtesting is nothing other than acceptance testing with the difference being the attitude of the player and the involvement of the developer in the process of testing. It’s effectively blending functional testing and usability testing into a single iteration of paired testing.

Makes sense. We've been pairing in software development, why not also do it with testing?

However, it lacked the element of play I was so interested in, except for the fact that you were testing a game rather than more serious work. So I invented my own playful test method by adding an element of play onto all the most effective test methods available — namely exploratory testing, mob testing and of course, usability testing — or play — testing.

After all, if it’s not a good user experience, nothing else really matters.

Let’s play!

Playful test can be used for anything, but is ideal for overly complex or complicated system design. When you have different devices, different personas each with their own dashboards, with a lot of variables and many to many relationships between different users or elements within the system, playful test outshines other methods.

For example, a rental agent management app has different functionality and information displayed on interfaces designed for tenants, agents or home owners. Each interface is in effect a separate system, with the user experiencing it as one integrated system. The platform allows each persona to have an optional and many-to-many relationship with a property. A tenant might, for example, be invited to join the system by a rental agent and a landlord at the same time. Or a tenant might sign up themselves and be an active tenant as well as a landlord. A property can be listed by multiple agents and the owner. Once signed up, there is a number of possible actions that can be performed in no specific order. In fact, all most of the rules can be broken in some way. A property can be occupied and available for potential tenants to view at the same time. A rental agreement can be terminated early, even though contractually there is a specified termination date. An agent can manage another agent’s property (or not). The list goes on.

When the requirements are fuzzy and the variables too many to list on a decision table, it’s time to play.

How to set-up the play-test

Playful test follows the basic rules of testing. Determine a strategy, spend some time planning what and how to test, execute and finally report the test results. The main difference in test planning is that there are no set sequence as in traditional planning with one test case following the next. Rather, it can be seen as playing with lego where each piece can be used to build many different things.

The first step is to create the different building blocks, starting with the personas and the scenarios.

Step 1 — Pick a personality

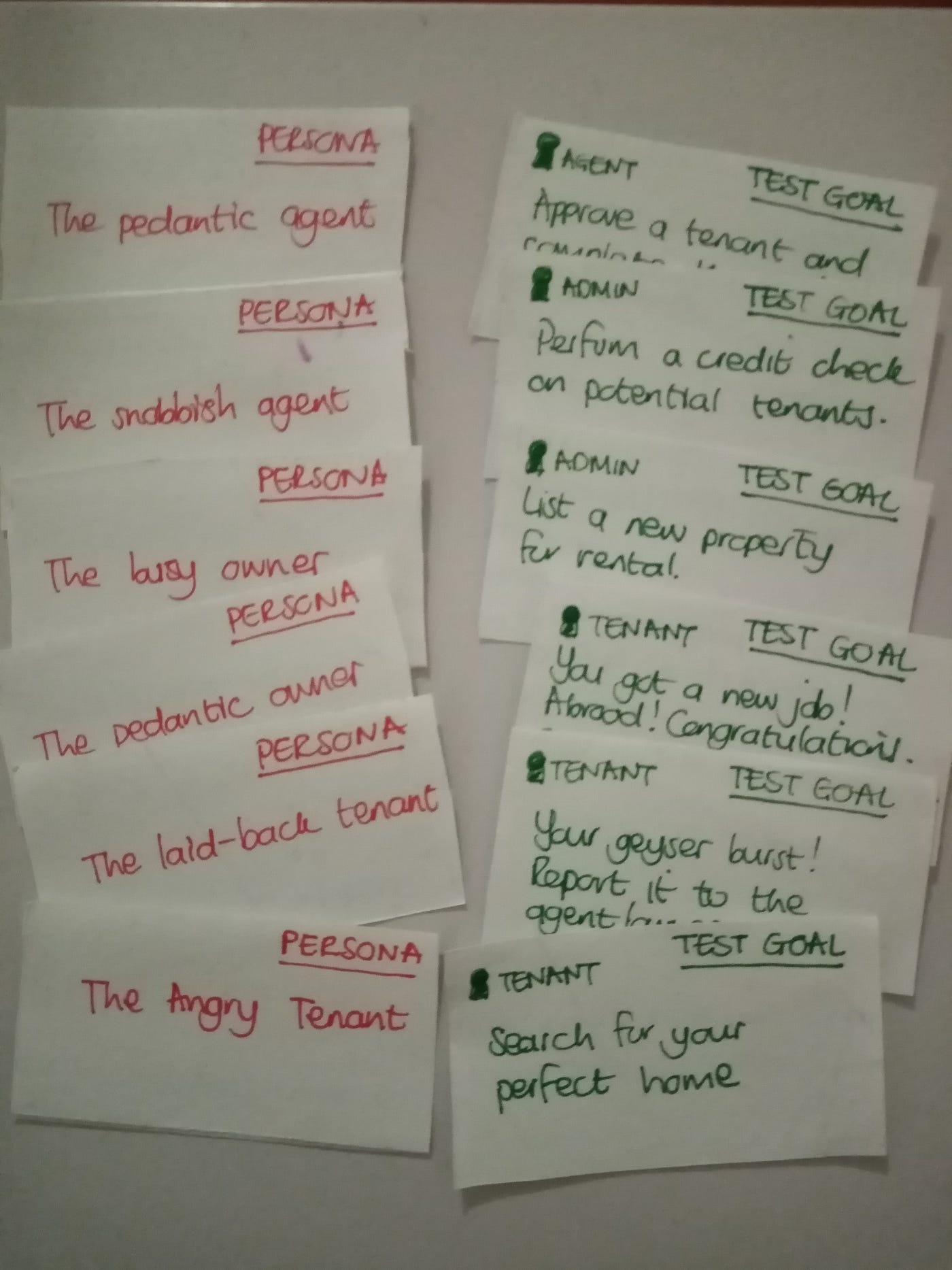

On small index cards, write the different persona types adding an adjective to describe the personality. For example the angry tenant, the snobbish agent, the busy landlord.

Adding an adjective gives more context to a user. It describes how they will interact with the system and what their unique needs are. An angry tenant might be impatient valuing speedy response times. A snobbish agent might be more pedantic in finding issues when doing an inspection, valuing details and accuracy. And a busy landlord might want to bypass parts of the workflow or do an action in a more efficient way than an agent, ultimately valuing efficiency.

This adjective is also the invitation to play. A mask the tester can choose to put on and step into the magic circle to become an imaginary person for a while.

But that’s all it is. An invitation.

There’s no such thing as forced fun.

It’s up to the participants to accept or reject this invitation freely and without any repercussion. A more playful tester might, for example, immerse himself totally into the chosen role, actively role-playing as a different persona to his usual personality. Another tester might not feel comfortable role-playing and simply act his normal self without any playfulness.

It's important to note that most teams are not ready to be playful if they’re used to a management and control type of environment. To be ready for play there needs to be a strong foundation of trust. To learn more about the prerequisites for play read The Rules of Play.

Create at least two cards more than all the planned participants to allow each person a choice (a crucial ingredient of play) and will ensure coverage.

Step 2 — Define test scenario’s and objectives

Next, based on the functions within the system, write down the test objectives — one per index card — for each scenario as you would in a usability test setting. Be sure to keep the objective cards separate from the persona cards (for example, using different colors or sizes for the cards).

For example, a tenant might want to search for a new home, or report an issue, or give notice. An agent wants to renew a lease, terminate a lease or do a credit check on a prospective new tenant. A landlord might want to list a new property, sign up a new tenant, or resolve a maintenance request.

For a more complete user experience evaluation, consider using the Game Thinking framework to help define all scenarios.

Low-tech is always more agile. Don't spend too much time trying to make it perfect, a simple handwritten piece of paper is much more flexible than a beautiful printed and laminated card.

Order and group these into small related groups and place them face down. For example, keep all sign-up and login related cases in one pile, all agent cases to list a property in another, cases to sign a lease in yet another, etc.

These cards will be your main play cards (action cards) during the play phase with players randomly picking a test objective or goal to perform.

Another basic ingredient of play together with choice is the concept of randomness. To create a more playful, and more realistic, test plan add random events (obstacle or challenge cards) on index cards and shuffle them into the main test object cards. Include an element of fun by adding, for example, a geyser burst, you got a job offer abroad and need to terminate your lease agreement early, or you — as agent — might resign and have to hand over your properties to someone else.

Step 3 — Team setup

Once you’ve prepared all the different index cards, it’s time to play!

Get the team together, consisting of at least the developers, business analysts (or product owners), designers and testers. Ideally, include a customer proxy and some third party users who has no relationship with the system. Aim for a representative, cross-functional team.

Break the group into 3–5 players per group and let each player pick a random role, ensuring each persona is represented per group. For example, each group has to have at least one tenant, while another might have 3 tenants and no landlord, or a landlord and agent etc.

Allocate different devices to different players to increase coverage and request each participant to use a different web browser. For example, one player might use a Windows laptop using Chrome, another an iPad, yet another a mobile phone with Opera as browser.

Make sure each device has screen capturing and recording software pre-installed and everyone knows how to use it to record and capture bugs easily.

Step 4 — Play time

Once all the logistics are sorted and everyone knows what to do, it’s finally time to play.

Allow each participant to pick a persona personality card and explain how to play. For larger groups consider splitting the group into players and observers, with the observers responsibility for observing the players as they play and making notes and log bugs as they occur.

With all the scenario (action and challenge) cards face down, let each player pick a card from the top of the pile and complete the test objective, while the scribe (and game master) walks around making notes while observing. Each player attempts to complete their test objective taking annotated screendumps or screen recordings where issues are discovered.

Don’t spend too much time on bug reporting, rather, get just enough information or record the entire session to allow for an uninterrupted play session.

Step 5 — Retrospective and closure

Once all the cards are finished, or when there has been sufficient bugs logged, wrap up the test session. In a round-robin fashion, ask for feedback and insights gained during play.

Consider adding a target consisting of 3 circles on a whiteboard for players to plot their perspective of system readiness (bullseye is ready to go, middle circle is close but not yet, and outer circle meaning there's still a lot of work to do). Ask for input as to where attention is most needed or what the next steps should be, translating this into backlog items.

The rules of the game

If your system under test is too complex or complicated to adequately cover with test cases, or if there are simply too many variables to test within limited time frames, consider adding playful test to your test strategy. The key to a playful experience is to provide enough structure to create an immersive experience while leaving adequate room for exploration and play.

Visit www.funficient.com to start the conversation to add play to your work, or read more about play here:

Design better products with Game Thinking

Originally written at https://medium.com/teal-times/testing-complex-systems-with-play-122760e03d00